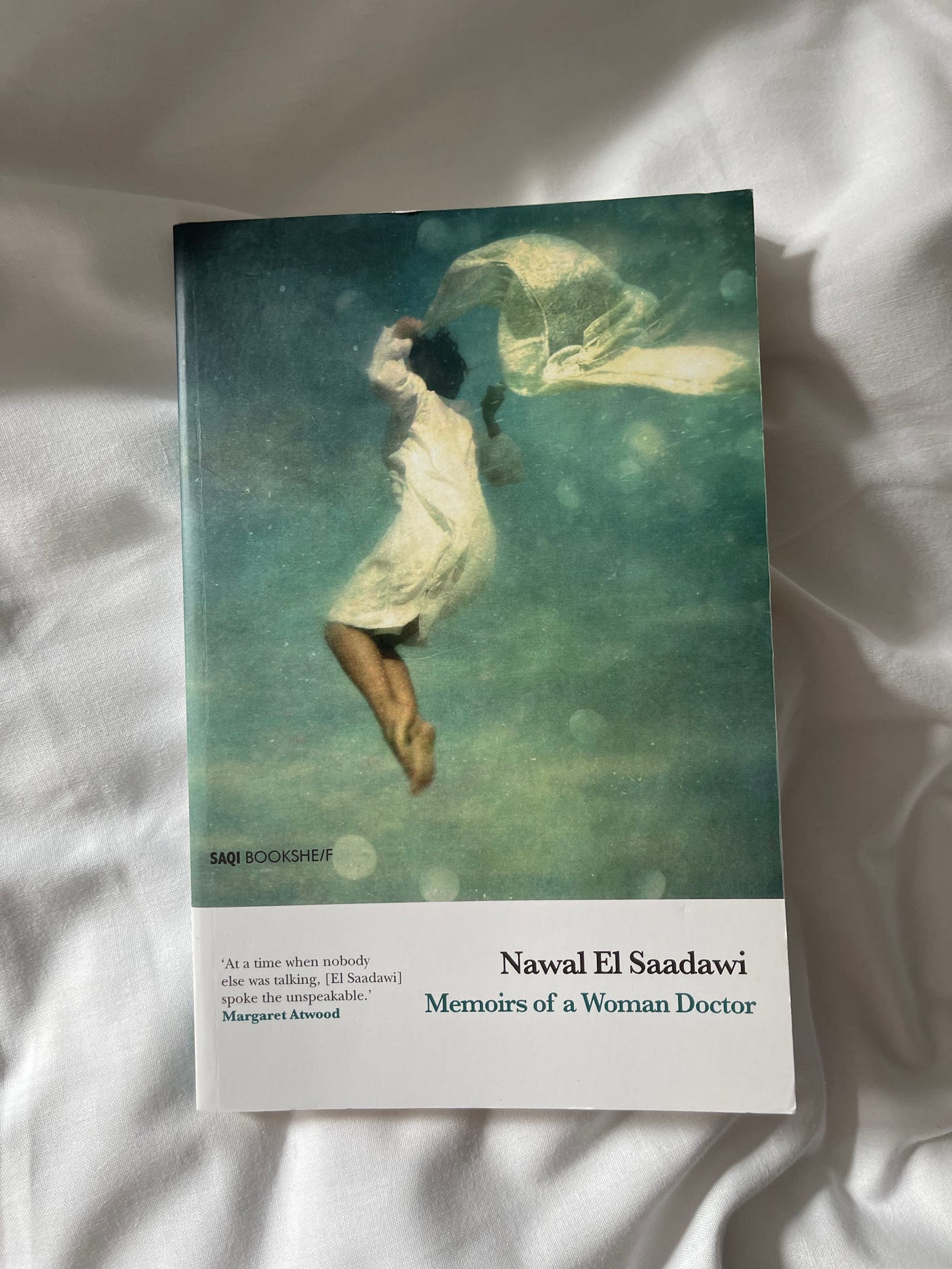

“Memoirs of a Woman Doctor (2000) was first published in its translated version in English in 1988. The Arabic original version first appeared in a serialised form in the Egyptian magazine Ruz al-Yusuf in 1957. The book was El-Saadawi’s first novel. In a preface to the English edition, she mentions that the book was censored both in the serialised and in the full book versions, but as she ‘was young and inexperienced and eager to see the book in print’ she ‘allowed it to be published with deletions’.”

Friends,

I absolutely loved this book! Even though the original Arabic version was written in 1957, it covers so many feminist issues that we still grapple with in 2023.

The original un-censored manuscript has been lost forever which is a shame, but the version we have still tells us enough about how deeply misogynistic and unsafe Egypt was for women in the 1950’s.

El-Saadawi was born in 1931 in Kafr Tahla, a small village in Egypt, the second of nine children. She won a scholarship to study medicine, graduated from the University of Cairo in 1955, and specialised in psychiatry.

Rebelling against the contraints of her family and Egyptian society, she decides to study medicine, becoming the only woman in a class of men. She realizes men are not gods as her mother had taught her, that science cannot explain everything, and that she cannot be satisfied by living a life purely of the mind.

It’s incredible how much I identified with the struggles Nawal mentioned in her book, even though we were born 40 years apart and on opposite sides of the same continent. Parts made me angry, parts made me sad. Overall though it’s a beautiful book written by one of the world’s most influential feminist writers and activists.

Some of my favourite paragraphs:

“Then I’ll tell you: because from early childhood a girl is brought up to believe that she’s a body and nothing more, so her body becomes her main concern for the rest of her life, and she doesn’t realize that she’s got a mind as well which must be looked after and encouraged to develop.”

“My brother played, jumped around and turned somersaults, whereas if I ever sat down and allowed my skirt to ride as much as a centimetre up my thighs, my mother would pierce me with a glance like an animal immobilizing its prey and I would cover up those shameful parts of my body.

Shameful! Everything in me was shameful and I was a child of just nine years old.”

“I was going to show my mother that I was more intelligent than my brother, than the man she’d wanted me to wear the cream dress for, than any man, and that I could do everything my father did and more.”